What is the Third Folio of William Shakespeare?

-

Ten years after the publication of the Second Folio, Civil War broke

out. The London theatres were closed and after seven years the

monarch, who had owned a copy of the Second Folio, was executed by the

parliament for the first and last time in English history. When the

English monarchy was restored in 1660 in the person of the eldest

surviving son of the executed king, London theatrical activities were

also resumed and Shakespearean plays, whatever forms they were

actually staged in, were among the early repertoires recorded in The

London Stage, 1660-1800 (Part 1:1965): Othello, Henry IV Part I,

Hamlet, Twelfth Night, The Merry Wives of Windsor and Romeo and Juliet

were to be found in the first three years of this new era.

This was the time when the Shakespeare Folio was printed for the third

time, which was also the first Shakespearean publication since the

Restoration. The years of the interregnum, roughly a period of twenty

years 1642-1660 saw only three plays and a poem in reprint anew in

contrast to twenty nine publications including the First and the

Second Folios (re)printed in prewar twenty years 1622-1641 according

to `Chronological appendix' in Andrew Murphy's Shakespeare in Print

(2003). This source also tells us that the next period of twenty years

starting from the Restoration 1661-1680 was to witness seven including

two issues of the Third Folio itself and Two Noble Kinsmen in the

Second Beaumont and Fletcher Folio.

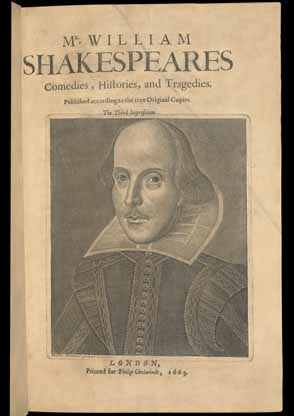

Third Folio, 1663 (MR 1938)

Philip Chetwind, the publisher of the Third Folio, had presumably

taken over the copyrights covering those plays which belonged to

Robert Allot by way of marriage to his widow and the copyrights

regarding the other plays were thought to be cleared through

negotiation with Ellen Cotes, widow of Richard Cotes, brother of

Thomas Cotes (Henry Farr, `Philip Chetwind and the Allott Copyrights',

The Library, 4th series, 15 (1934-5): 129-60).

The printing of the Third Folio carried out by the shared effort of

three printing houses is that of ` page-for-page reprint of the

Second Folio so far as the text is concerned' as W.W. Greg describes

it. The layout of the preliminaries are changed although the materials

are identical: Milton's poem as well as Digges's are laid out so as

to occupy one whole page each.

In 1664 Chetwind published the second issue of the Third Folio.

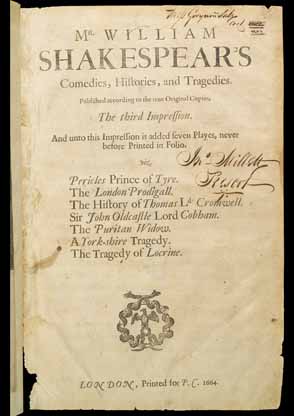

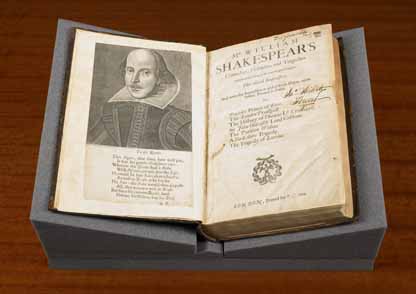

The Third Folio, Second Issue (MR 733) [Image # 11]

In the second issue, Chetwind added to the volume a hundred-page new

section that consisted of the seven plays, viz., Pericles, The London

Prodigal, Thomas Lord Cromwell, Sir John Oldcastle, The Puritan, A

Yorkshire Tragedy, and Locrine to list in the order of

appearance. These plays had already been printed earlier in

Shakespeare's lifetime with such title page announcements as

`Written by William Shakespeare' or `Written by W.S.' Pericles has

since been established among Shakespearean cannon while the other six

plays are now considered apocryphal.

The enlarged publication of play text in the folio is not without

examples: The Ben Jonson Folio was first published in 1616 and was

enlarged and published in 1640, which in turn was reprinted in

1692. The Beaumont and Fletcher Folio first published in 1642 was to

be enlarged and published in 1679. Publication of an enlarged edition

would promote purchase even from the owners of the original

edition. It is a well-known episode that the Bodleian Library sold a

copy of the First Folio to acquire the Third. (The discarded First

Folio copy fortunately has since found its way to be restored in the

holdings of the Library.)

W. Black and Matthias A. Shaaber in their Shakespeare's

Seventeenth-Century Editors, 1632-1685 (1937) found ` total of 943

editorial changes' as well as `an equal number of corrections of

obvious typographical errors and of improvements of the punctuation'

and fairly consistent spelling modernization (p. 50). In order to

illustrate a little about the Third Folio's editorial work, let us

quote two examples from their findings, both happened to be from As

You Like It. One is from Act IV Scene iii where Ganymede/Rosalind

swoons seeing the `apkin, / Dyed in [Orlando's] blood'.

Aliena/Celia cries out:

| F1,F2 | There is more in it; Cosen Ganimed. |

| F3 | There is no more in it; Cosen Ganimed. |

This change, though not retained after Theobald's edition in 1733, is

nonetheless defendable, Black and Shaaber write, because it is done

"on the supposition, presumably, that it is dramatically

inappropriate for Celia to excite suspicions in Oliver's mind, that

she should, on the contrary, protect Rosalind's disguise and try to

allay them" (p. 55). Arden 3 (2006) edited by Juliet Dusinberre

reproducing F1 reading cites Dr Johnson's note here: "Celia's

agitation leads her to forget to act the part of Ganymede's sister."

The other is from toward the end of the play. Hymen brings to the Duke

Senior Rosalind and Celia presumably undisguised and says in the last

two lines of his first speech:

| F1,F2 | That thou mightst ioyne his hand with his, |

| Whose heart within his bosome is. |

| F3 | That thou mightst joyne her hand with his, |

| Whose heart within his bosome is. |

This is adopted by the subsequent editors and Arden 3 cites the Third

Folio in its critical apparatus although Dusinberre is cautious enough

to cite Jeffrey Masten's argument `that [the First Folio's] `his'

is a deliberate recognition of the `joining' of Orlando with a boy

actor, which would suggest that Rosalind is not wearing wedding

clothes' in her foot notes.

August 31, 2007

|